Electric Vehicles (EVs) have occupied a lot of media space of late and are widely regarded as the next big breakthrough technology in the automotive world. Though EVs are as old as motor vehicles themselves, they lost the race to Internal Combustion Engine (ICE) vehicles, running on liquid fuel, by the early 20th century.

But with the rising threats of global warming and air pollution, EVs are back on the discussion tables of policymakers. ICE-powered conventional vehicles emit several pollutants, among which CO2 (a Green House Gas) is considered as the most dangerous pollutant from a climate change perspective.

The CO2 Context

India is the third largest emitter of CO2 in the world, behind China (almost 4x of India) and the USA (2x of India), with its annual CO2 emission doubling in the last decade. Though India’s contribution to the cumulative global CO2 emission, since the industrial revolution of the mid-19th century, is insignificant, its current position as an emerging economy and hence a big CO2 emitter comes under environmentalists’ lenses.

Ever since the formation of the United Nations Framework Conventions on Climate Change (UNFCCC), India’s position has been to put its socio-economic development above the resultant CO2 emissions and refraining from putting itself in the same carbon-reduction target brackets as the developed nations. Nonetheless, India has been an active and important party in all global climate action summits and conferences, negotiating for emerging economies, who came late to the ‘development’ party.

This stance remained, more or less, consistent until 2014 when a new government came to power that had intentions of not only being a mere party in global climate action strategies but of taking leadership position. Eventually, India ratified the Paris Agreement during the COP21 held in 2015 and pledged to reduce the carbon intensity of its economy by 33-35% by 2030 compared to 2005 levels and committed to achieve non-fossil share of cumulative power generation of 40% by 2030. It also announced to install 2.5-3 billion tonne of CO2 equivalent carbon sink by 2030.

Transport sector accounts for a quarter of the global CO2 emissions, and three quarters of this come from road transport (cars, motorcycles, trucks, buses, lorries); so, naturally the focus of policy makers and environmentalists is on this sector. Therefore, any method, which promises reduction of CO2 emission from this sector, will find interest from policymakers, industry stakeholders and investors.

As of yet, electric vehicles with propulsion power derived from rechargeable batteries and having zero tail-pipe emission, are considered to be the saviour for this sector.

India and its EV policies

In 2013, under the National Electric Mobility Mission Plan (NEMMP), it was envisioned to transform the mobility landscape in India and make electric vehicles an important part of it. As a result, a new EV promotion scheme was being worked out by the Ministry of Road Transport & Highways (MoRTH).

By the time it was rolled out in April 2015, it was named Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of Electric Vehicles (FAME) scheme and a new government was in power. The creation and expansion of the low-speed e-scooter segment aside, the Phase 1 of FAME (April 2015 to March 2019) did not exactly produce the results as intended.

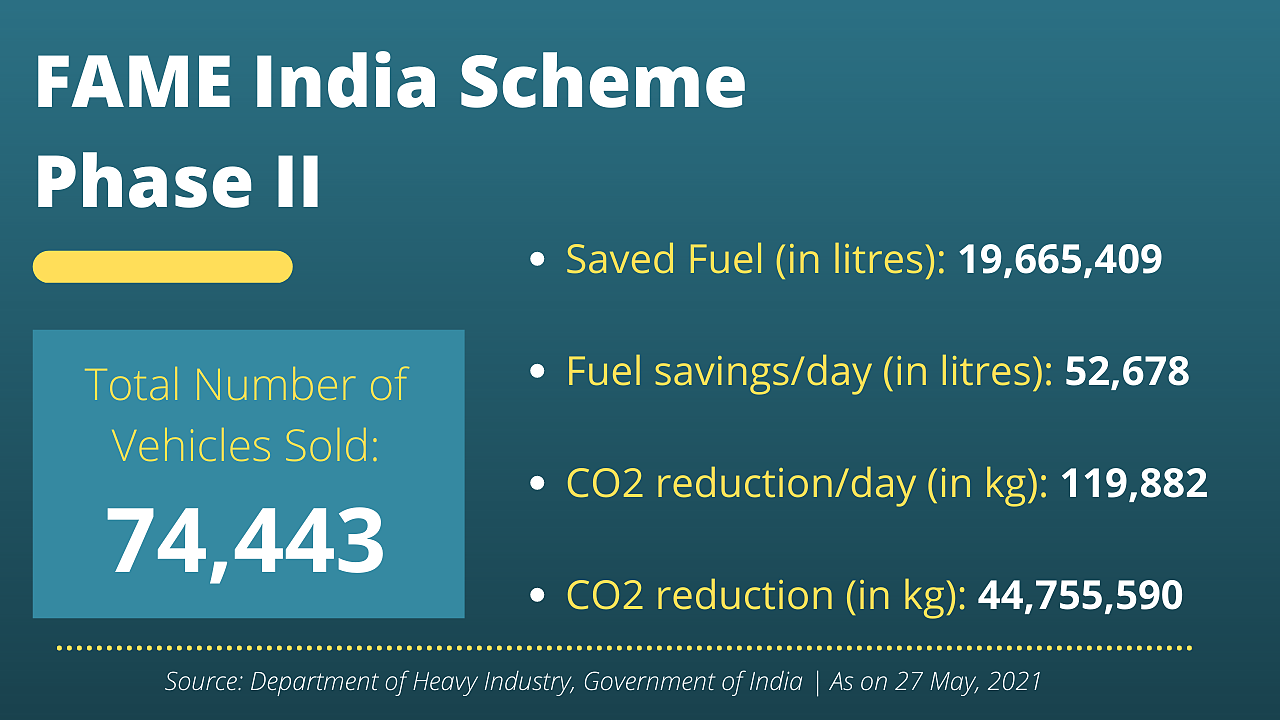

Considering India’s Paris Agreement goals and COP21 commitments, the government redesigned the Phase 2 of FAME scheme – an outlay of INR 10,000 crore over three years starting April 2019 and focus on 2W/3W/Bus segments that move about 85% of the people of India.

Simultaneously, EVs were brought under the 5% bracket of GST to entice OEMs into launching new EV offerings and an additional income tax reduction clause was introduced as additional incentive for prospective EV buyers. However, two-third of the time horizon of Phase 2 has gone by and merely 2% of the total outlay for this phase got utilised.

In this period, the sales figures tell a sorry tale – less than 10,000 electric PVs and less than 300,000 electric 2Ws were sold. To put it in context, the total sales of PVs and 2Ws in this period were 5.4 million and 32 million respectively. If there was a contest for government policy making and implementation, it would not be unfair if the FAME policy was judged poorly. The policy support by several State governments didn’t help too much either to stimulate EV demand.

There is another key inference that can be made from the slow uptake of EVs, that there is no organic demand for EVs in the Indian automotive market yet, and hence fiscal support and policy interventions would be essential to enable the transition from ICEs to EVs. However, policymakers must be sensitive to the Indian automotive industry’s concerns and appreciative of the unique challenges of this market.

Reducing vehicular CO2 emission

Transitioning from ICEs to innovative technologies, including EVs, can be a crucial pathway to reducing CO2 emissions and other negative externalities arising from fossil-fuelled vehicles.

To regulate and limit CO2 emissions from vehicles, the Corporate Average Fuel Economy (CAFE) norms were introduced. The Phase 1 of CAFE has been in place since April 2017 and Phase 2 is about to kick in from April 2022. These norms are technology-agnostic and primarily aim to force OEMs to reduce their fleet CO2 emissions.

Though these norms do not incentivise the demand side, they do influence the supply side by encouraging automotive OEMs to introduce CO2-reducing technologies in their products. Electrified technologies like mild-hybrids, strong-hybrids and pure EVs get special volume derogation factors for availing super credits. In simple terms, this means that having electrified-ICEs or pure EVs can ease an OEM’s CAFE compliance pathway.

According to the latest FE values released by SIAM, all car companies have complied with Phase 1 targets. Some OEMs are so close to the Phase 2 targets that it appears they may achieve Phase 2 compliance without much incremental effort. This could mean that either the OEMs’ FE strategies are very well aligned with the regulations or maybe the regulations themselves are not stringent enough. Moreover, there are no punitive actions for non-compliance.

And that is where policymakers have room to improvise to make the regulations more effective. Instead of five-year-long phases, there could be yearly assessments of the industry’s CO2 performance, based on which the successive year’s CO2 targets would be fixed. The idea is to have a certain percentage drop each year of the industry’s average fleet CO2 with an additional clause of monetary penalty for non-compliance.

Thus, OEMs will have clarity about the policy for a longer horizon and would be in a more certain position to make the relevant investment decisions into CO2-reducing technologies. Eventually, pure EVs would become essential part of the OEMs’ sales mix for them to be in compliance. Moreover, if the CO2 regulations are integrated with the EV promotion scheme (FAME), then the outcomes could be even more efficacious. Of course, this is made to sound too simplistic and would need deeper deliberations, but it would be absolutely worthwhile.

Policymaking as an enabler

The automotive industry contributes about 8% to the nation’s GDP and almost 50% to the manufacturing sector’s GDP, employing millions directly and indirectly. Abrupt policy interventions and lack of long-term regulatory roadmap hamper the growth prospects of this key industry. Climate change is real, and the automotive industry must play its due part in this fight. But it would be imprudent to negate the contributions or curtail the growth opportunities of a key industry by forcing short-sighted policies.

The good old carrot (strong FAME) and stick (stringent CAFE) kind of policy will work just fine in limiting the transport sector’s CO2 emissions. Additionally, the recently announced PLI scheme on manufacturing of advanced batteries will also provide some boost. Government officials and ministers should exercise caution in making overtly ambitious EV goal statements in the media or avoid any comments on EV transition timelines as it triggers panic and uncertainty. And it’s well established that any form of uncertainty is unhealthy for businesses and adversely impacts long term investment potential.

EVs are no longer considered a disruption but an eventuality waiting to happen. The automotive industry is very aware and provident, policymakers must respect its longer product lifecycles and even longer RoI periods, and the unique market challenges it has to overcome to remain sustainably profitable. This industry has been a shining star of the India growth story and still has a colossal potential for growth, policymakers must ensure that it is fulfilled.

About the Author: Suraj Ghosh is Associate Director, Powertrain & Compliance Forecasts, South Asia at IHS Markit.

Note: The article contains the author’s personal opinion and views, and doesn’t reflect his organisation’s position in anyway.