About six years ago, I had stepped-off most of my full-time corporate and board roles to look at what the future of the auto industry would be. I wanted to write a book with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) in Boston, but very quickly in the research we found out that, frankly, there was no point in writing a book just about the auto industry.

The whole industry was transforming very rapidly into what should be mobility. We changed our focus to write this book about the future of the car and urban mobility, because that was the only relevant topic of discussion that we could see from our research across global regions.

The reason why we said this is going to be particularly relevant for the urban context, is that by the middle of the century, four out of every six persons on the planet would be in urban space. We have to deal with the other context where people are going to be increasingly living their lives and going to work.

And if you look across the world, no matter where you are, the urban priorities today are –

- How do we have clean air in our cities? We know this is a critical issue in India;

- How do we make better use of very valuable real estate? The typical car occupies 10 or 15 square metres of land space, occupies land that could half a million dollars if you are in New York or London or Paris. That’s very expensive real estate. So, you've got to find ways to share the space.

- We've also heard about congestion, the fact that cities can't take any more cars or even two-wheelers. And finally, we've had a lot of research around the world that says the average car is used for about 5-6% of its time. This means for 95% of the time, an expensive asset is idle.

If we take all the three elements together, we as a society across the world have to find better ways to share the carbon footprint, meaning share the fuel and the greenhouse gas emissions, to share the real estate and space, and to share the economic asset, you have to find convergence of all of this and this forces one to start to think about mobility as a solution, not just the car.

This is not surprising because how often do we use the word telephone anymore? We call it smartphone, use WhatsApp, and do FaceTime. This is the transformation of what used to be a telephone into such a wide variety of communication aids.

So, there's no reason to believe going forward that the definition of mobility will be anchored just by the definition of what an automobile is. We began to see in our book and we created a framework for this saying, very likely, the future of people moving about would require multi-modality. This means everything from walking on some journeys to micro-mobility options all the way through shared rides and travel on a Metro rail.

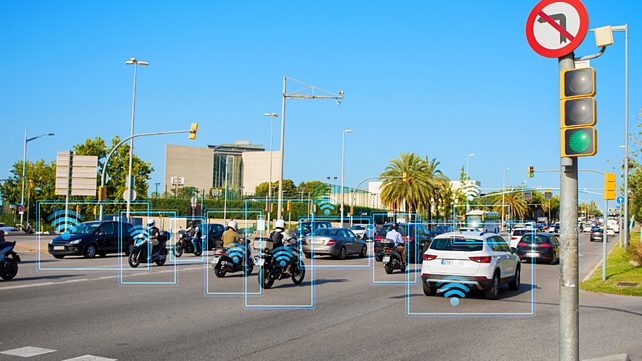

Mobility modes will be highly connected, because these are going to be very well connected to each other; they will be intelligent, because we're going to apply intelligence in the tools that we have in our pockets, namely the smartphone, and tools that we have in our vehicles and intelligence that would to deployed in city infrastructure and systems.

We will all expect personalised services. How I travel to go out for dinner with my wife on a Sunday evening will be different from how I want to go to work on a Monday morning. It has to be personalised to the individual and the context.

So, if you put all this together, there is no reason why we would continue to anchor our definition of transportation around just the automobile. Just as we've made the transition in communication, we will make the transition to go from thinking about cars to a very rich, very productive, and hopefully sustainable spectrum of solutions in mobility.

I commend Mobility Outlook to have launched this initiative. It's a very timely transition to a new dialogue with new vocabulary.

Coming Together Of All Stakeholders

We must accept that the problem we're trying to solve impacts the intersection of consumers, government – essentially the representatives of society responsible for regulations and policy making – and industry players, whether it is manufacturers of vehicles, or providers of services; take Uber, for example. I think, this intersection is really what we have to start to look at.

We have examples at two very extreme ends. Los Angeles is a wonderful example of letting the industry go ahead and do whatever it wants, and the city building roads to catch up. This has been a disastrous trajectory. Los Angeles has the most roadways square km per inhabitant, it has the most number of cars per capita, and it has the worst congestion and the worst air quality among any of the large cities.

So, it's not a trajectory that's taking us to a meaningful future. Then you start to see cities like Singapore and even London and increasingly Hong Kong and Tokyo. They have addressed this issue of dealing with a lot of people by altering dynamics between what the society wants, a very proactive policy making and regulatory regime, and very quick adoption of the right kinds of technologies that serve this population.

And most recently, COVID-19 it has somewhat shaken up a lot of our assumptions going forward. We’ve got a new set of filters and factors to consider as we re-architect mobility. And this one's going to be based around proximity. Will people want to get into a crowded Metro train, or be in ride sharing cars in close proximity with people?

This means we must deploy technologies like micro-mobility, whether it's scooters or micro cars. The interplay between what consumers want, what is good for the society and how we play with the dynamics of technology, is perhaps the most important thing.

Learning For India

Urban planning and urban architecture are of critical importance. We can’t solve the mobility problem without solving the urban architecture and urban planning problems. My biggest fear is, too many Indian cities are going the trajectory of Los Angeles. We have very poor planning, there is uncontrolled sprawl, and there is unstructured expansion of the city boundaries.

Many cities have recognised this problem and they've actually curbed it. London is a great example. They had the green belt around London and they said they are going to force the densification of London. The moment you force densification, you're able to provide better quality infrastructure at better capital efficiency. This is why a city like Singapore can serve its citizens very well because infrastructure is delivered with greater capital efficiency to such a population. Now, this is a very important thing that we have to learn in India.

After COVID, we're now going to one more stage of urban planning. Paris, for example, is talking about a ‘15 minutes’ city. They want to make multiple clusters of economic and people concentration around the city. It’s like creating multiple satellite cities, wherein you will have most people live and work within those satellite cities, and there will be limited transportation required, considering schools, hospitals, and offices will all be within the boundaries of these satellite cities.

These are new ways of looking at urban architecture and saying, can we find better ways to minimise the load on transportation, which is increasingly energy inefficient. At the same time, there are these other concerns about people proximity, economic efficiency and so on.

So, the Los Angeles model is certainly not the model for us to follow. Unfortunately, it is a model of default. Till the time infrastructure does not anticipate demand, we're going to have this problem.

India is not like China. We can’t say we would build infrastructure and then populate the region. We can't afford that kind of capital. We have to be a lot more careful in planning, and be proactive in what needs to be done.

Spectrum Of Solutions

When we talk about transformation and mobility, we must keep in mind that there is a full spectrum of solutions. Actually, one of the points we make in the book is that you can't even talk about the mobility architecture for a city without decent pavements and sidewalks. If you want multi-modal mobility to work, it starts with very simply solutions to get people to walk. Too many of our cities have made it impossible for pedestrians to safely use roads.

It’s not just a question of hi-tech, but a question of being sensitive to this combination of mobility requirements. The second example has been very well articulated by Enrique Peñalosa, the former mayor of Bogota, Columbia and a very famous urbanist. He said, people seem to think that an advanced country is one where even the poor people can travel by cars. But he said, a developed country is really one, where even the rich people take a bus or train to work.

When you see poor people owning cars in rural Texas, it is no big deal, but look at Copenhagen or Amsterdam, where rich people use public transit and walkways and bicycle. I think, we have to change a little bit of our mind-set – about what is progress, what is technology and what is advancement of our environment.

The second aspect of this is also going to be the spectrum of solutions available. Bicycles are something that we have neglected. Non-motorised transport is an important element of the architecture of the cities I've talked about. It's not sophisticated to bring these back in the Indian context. Bicycles used to be a very popular mode of travel in many cities. Somehow we followed the Chinese example and abandoned bicycles. We’ve got to make them fashionable again.

Tesla made electric cars fashionable. Before that, we had small little electric city cars and micro cars that were not really capturing the imaginations. Tesla made electric vehicles fashionable. Fortunately, we have an opportunity to make bicycles fashionable; not just plain bicycles, but bicycles with perhaps even electric assist.

When we imagine the full heterogeneity of mobility and mobility modes – everything from walking, bicycles, e-bikes, scooters, and the whole spectrum beyond that – people realise that we can actually synthesise the kind of architecture that our cities need. This doesn't mean that we have to have very expensive solutions.

India is going to be an affordability-constrained economy, as far as mobility is concerned. We can’t ignore that aspect of the architecture we need. But if we are imaginative and we make the right kinds of investments, right from starting with pavements, sidewalks and pedestrian crosswalks, I think we can get what we want within the affordability that a country like India has.

About the Author: Dr V Sumantran is Chairman of Celeris Technologies. He is an Adjunct Professor at MIT-MISI, serves on the Board of Governors for the Indian Institute of Technology, Ropar and on the Advisory Board of the Fraunhofer Institutes (Germany).