The pandemic has worsened the shortage situation in the chip industry. The recent shortages of semiconductors have been hammering automakers and its immediate ecosystem. An estimated four million vehicles will be lost in 2021 because of the shortage.

This growing automotive semiconductor demand is competing for capacity with other rapidly growing industries: consumer electronics, home gaming and power electronics for renewable energy solutions, to list a few. The computer chips in highest demand are not particularly sophisticated or expensive, but they’re vital components used in everything from kitchen appliances to washing machines and electronic gadgets.

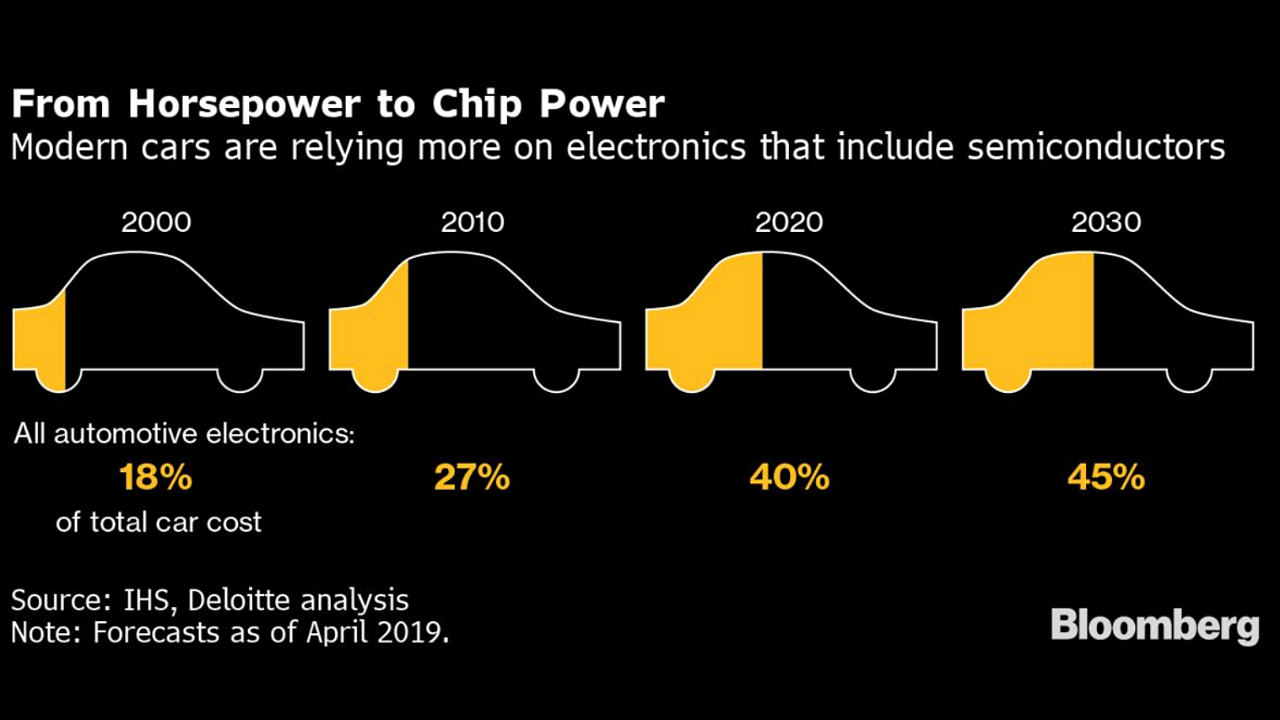

The average car uses several hundred chips. These are used in a growing number of applications, including driver assistance systems, conventional features, safety aspects and navigation control. In addition, the recent shift to electric vehicles and growing charging stations is happening faster than anticipated, which has added to the increased demand for automotive chips.

The current situation is raising innumerable questions about raw materials, demand management, sustainability, policies, investing patterns, launching new models, and e-commerce.

The biggest question, however, is with respect to the leeway of scaling-up the production of these chips. Though it is not technically inhibiting, it is extremely tough and requires lead time with huge investments.

Complex structures

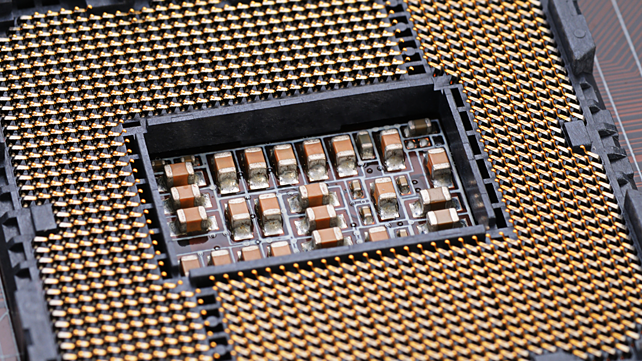

Chips consist of multiples of 10s of layers of materials. The complex layered structures that connect tiny transistors need to efficiently manage a range of variables, such as temperature, pressure, and electrical and magnetic fields. The upper and lower limits of these variables could change depending on the application/deployment of the chips but generally they fit in the normal distribution curve.

To meet these strict operating expectations, chips are manufactured in dust free ultra clean rooms, using automated smart machines, lasers, gizmos and could take more than 12 weeks end-to-end. Experts say that ‘the end goal is to transform wafers of silicon – an element extracted from plain sand – into a network of billions of tiny switches called transistors that form the basis of the circuitry that will eventually give the consumer crucial capabilities’.

Industry experts say that chips are complicated devices that require mega-investments that could run into billions of dollars. The miniscule lack of efficiency in manufacturing expertise can throw off the math, while competing with other manufacturers. The EU, the US and China are making it their top priority to build a secure supply chain that has robust efficiency of resources.

Analysts gather that ‘the chip shortage makes it essential for supply chain leaders to extend the supply chain visibility beyond the supplier to the silicon level, which will be critical in projecting supply constraints and bottlenecks and eventually, projecting when the crisis situation will improve’.

For smaller OEMs, it may be prudent to create strategic relationships with distributors, and retailers that can help with finding small volumes for urgent components.

The current crisis also exposes a basic mismatch in the supply chains of automotive industry and semiconductors. The automotive just-in-time paradigm fundamentally does not jive with the long manufacturing cycle times and ordering lead times in the semiconductor industry. Challenged with this shortage, many OEMs have gone back to analogue models or reduced the interactive features and options, thus decreasing the number of chips being used in vehicles.

Addressing the price challenge

The challenge now is the price increase of vehicles, where more than 50% consumers are paying about 5% higher price. Data shows that even though demand for consumer electronics and cars tends to be quite price sensitive and is likely to moderate with even modest price increases, it is estimated that reduced supply could boost prices by 1-3% in affected categories.

The market is expecting that the current chip shortage will go beyond 2021. The inherent supply and demand imbalance will remain since there is a lot of catching up of the gestation period. Demand will continue to rise and may not be met due to the lead time for projected capacity increases.

The seriousness of the situation forces all players, OEMs and Tier 1s, to tackle the chip crisis collectively within the larger ecosystem. The ‘chips for mobility that matter’ will have to be viewed and handled more strategically, for a sustainable mobility ecosystem.